Unless the readers of this article have been in purdah for the last few days, they will be aware that President Putin held his annual Q & A on Thursday 19th December. Clocking in at over 4 and a half hours, Putin answered 76 questions, comprised of the usual mix of geopolitical commentary, domestic detail and the odd softball heart-warmer.

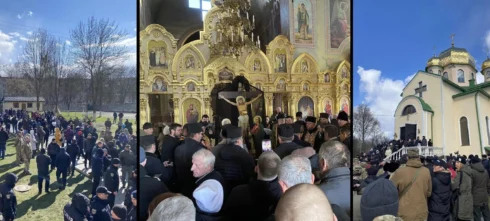

It is entirely natural that much attention was devoted to the ongoing SMO, but my concern is to highlight Putin’s statement on the plight of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC). The UOC is a branch of the historic church which straddles territory that was once united in a single empire, but is now divided into the separate political entities of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. As it remains faithful to the Moscow Patriarchate, the UOC has been systematically persecuted since the Maidan coup of 2014 brought an overtly anti-Russian regime to power in Kiev, with churches and monasteries being closed, raided and even bombed, and clergymen harassed, prosecuted and sometimes murdered, particularly in the Donbass.

This reign of terror only accelerated in 2019, when a schismatic Ukrainian church was hailed by the Patriarch of Constantinople as the ‘true’ UOC, and then further intensified since the beginning of the SMO. The UOC has been accused of being a Trojan Horse for the sin of Russianness in Ukrainian society – the same society that is largely Russian-speaking, and at least 50% ethnic Russian – and is now used as a stick to beat the majority of Ukrainians who fail to hate Russia enough to abjure the faith of their ancestors. This is despite the fact that the Moscow Patriarchate has never made any political demands on the Ukrainian faithful which might constitute a challenge to the Ukrainian government.

Putin, usually circumspect in his criticisms, was uncharacteristically vociferous.

“You know, what is happening to the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine is unique. Simply unique. It is a gross, just blatant violation of human rights and the rights of believers. The church is being torn apart in front of the whole world. It’s like a firing squad. And everybody in the world prefers not to notice it.”

“I think those who are doing it will have it come back to them. You said they’re tearing it apart. Yes, that’s what’s happening. You see, the thing is? They’re not even atheists, these people. Atheists are people who believe in something. They believe that there is no God. But that’s their belief, that’s their conviction. And they are not atheists. They’re just people with no faith at all, godless people…They are people without family, without tribe, they do not care about anything that is dear to us and to the overwhelming majority of the Ukrainian people. They will go to the beach, not to church. But that is their choice…”

Anyone who has watched any of the plentiful footage of the persecution of Ukrainian Orthodox Christians will understand Putin’s emotional outburst. The visible distress of the congregation, as soldiers break into churches, burn icons and beat up priests, is hard to stomach, particularly as so many of the people are either very young or very old. At first glance, it is natural to cast those who attack old people, children and peaceful priests as cynical, faithless and mindless. However, although Putin’s desire to disparage the perpetrators is a natural one, it is hard to see his words as anything other than rhetorical.

Putin, as surely the most historically-minded of all world leaders, will be keenly aware of how Ukrainian nationalism, in its most virulently anti-Russian form, is rooted in an emotionalism that is certainly religious in its mesmeric power. As any student of eastern European history knows, the area now known as Western Ukraine, the root of Ukrainian nationalism, was part of what the scholars Omer Bartov and Eric D. Weitz called ‘the shatterzone of empires’; an area, populated by incompatible peoples, that has changed hands repeatedly, creating a kaleidoscope of constantly-shifting power imbalances and mutual antagonisms. Russia, in the form of the old Tsarist empire, the Soviet Union and then the more recent Federation, is merely the last in a line of regional hegemons to trigger feelings of fear, envy and hatred amongst rival ethnicities, and in particular those Ukrainians who evolved an elaborate mythology of genetic and cultural superiority to their neighbours in order to combat their feelings of impotence and rage.

To imply that those now acting against the church lack any systematic framework of motivating belief is to ignore the results of this mythology of difference, which has developed an elaborate superstructure of creation story, exegesis, catechism and ritual similar to that of a conventional faith. This is not to imply that they are at all original; the solemn torch-lit marches, the invoking of the psychopath Bandera as a Christ-like figure, and the constant exhortations of ‘Slava Ukraini’ are almost totally derivative of a certain notorious period of history. To those of an emotionally-healthy disposition, they seem at best ridiculous, and certainly more reminiscent of self-delusion and failure than glory. But to a specific kind of Ukrainian, raised on an IV drip of anti-Russian outrage, they are quasi-religious practices that are just as sacred as the Orthodox sacraments.

Here a disclaimer is important; clearly it is not possible to discern the exact motivations of all those participating in the persecution. Some policemen and soldiers may be too apathetic to do anything other than go along to get along. Some may even feel too frightened to resist their orders. Conversely, others may be genuine satanists who will take any opportunity to attack any church! To echo a famous British queen, we cannot make windows into men’s souls, but we can make educated guesses about the dominant motivation, given the plentiful evidence available. Putin has every right to disparage the ‘godlessness’ of those who attack the Orthodox faithful, but it is not quite correct to call them faithless.

MORE ON THE TOPIC:

this is the legacy of the battle against the khazar empire🥶

unfortunately, putin doesn’t seem to understand that the judeo masonic cabal is the one behind the plan to conquer and balkanize russia. by judeo, for those that are illiterate — i mean the jews.

you’re just silly like all nazis .imo .

putins no fool he knows whose who in the zoo and president of khazaria was his best friend .curiously though ,what was her name the rich girl billionaire who was flavour of the month with the windsor’s , what was her flipping name , so annoying ,anyway is disappeared rather like assads wife, former city banker and very congenial.with qe2 seems set to.do too .

silly prattle indeed.

putin is a thrall of chabad. phony as a 3 dollar bill.

chabad gtp posts garbage like this all the time….

they are true believers in preemptively decapitating the leaders of those who resist them. i wonder when putin will come to the realization that it is part of an effective asymmetrical combat strategy and participate in the concept by bringing it to them. just eliminating their brainwashed useful idiots is not dealing with the decision makers who helped create them.

you end up with leaderless resistance and then fall into the infamous…

будь геем, совершай преступление

thin line between a band of brothers fighting injustice and the gay mafia.

look at roy cohn and trump…..

leonard cohen – first we take manhattan(detroit house remix)

you are retarded.

actually it goes back to 1054. the byzantine christians (origin of orthodoxy) refused to agree to the supremacy of the pope so he excommunicated all of them. the holy roman empire has been trying to conquer them ever since. charlemagne, napoleon, hitler and boris johnson – and countless others – were/are all catholics.

countless others were catholics? no shit, sherlock.

the most powerful members in both the republican and democratic parties are. many of the the eus leaders are as well as obviously australia new zealand canada

etc and in africa too .most of you tubes presenters are joe rogan and most if you look as well as almost every fox presenter which is catholic owned as is sky news etcetera.

so are almost all other news sites and the moderator’s they’re all doing the same thing attacking the existing world order and coming at the wotld from every angle ..imo .from observation .

btw in his xmas address apparently according to our msm national tv news the pope has likened a gossiping nun to a terrorist and called gossip something inappropriate. so now silencing the church from within too imo .

btw zero fudge and inspo views epic crimes and so forth are too imo .

such rubbish from my dads dad i’m khazarian but from iran persia , originally , and it’s a load of bollocks imo .

putin is part of this empire… he is depopulating ukraine. why didn’t putin fight this regime when it was still weak?? what are the rabbiners of the chabat sect doing with putin in the kremlin? etc…. the pro-putin propaganda is as bad as the pro-zenelsky in the west.

no, it’s really not.

there’s truth in what you say they are using it all to destroy the peoples trust in everything old except themselves .imo .in democracy freedom liberty identity archetypes of ages everything that’s been normal .private property inalienable birth rights everything all being eroded and replaced with their new plan .imo

what a crock of $hit the ex-kgb turned billionaire western anglo-zi0ni$t puppet that he truly is. waiting patiently for his bank account($) to be un-frozen and playing the western establishments game all the while to repatriate his and his associate($) dragging the war out in ukraine and abandoning syria as some sort of good conduct metal for not turning the west’s project inside-out in the hopes of getting it all back!…

…when you gamble and place your bets and “lose” -you lose with dignity and -move on!… if ever there was a time for true leadership to be found in this most important sovereign nation at it’s most important time and place in the world. but if he had it. he would have done it 23 years ago when he knew the cards he was holding on 9/11/2001.

jews did it to escalate war in middle east by destroying irak. putin knows that but putin also knows lot of “russian” billionaires are part of the tiny hat people tribe. going after them means destroying the ussr narrative about ww2. this narrative is still used today to recruit russian soldiers and justify the smo.

russia would be so much better off with out any of the cabalist nonsense, including all the multikult soviet crap.

one of the only groups putin regularly attacks are the russian nationalists, what makes it totally infuriating is he literally celebrates and arms the chechen and tartar nationalists.

yes it’s all very convoluted by design. it’s difficult but there’s common threads .

the russian ww2 narrative is relatively accurate, at least in comparison to the one peddled by the five eyes.

nothing is more silly than writing in english as the global language about the jews did it.just dumb .imo

you’re right of course. is this why putin is also pro-i$rael that he felt that the sacrifices that his country made in syria 10 years ago were worth leaving it to be fed to the dogs in return for nurturing those “tiny hats”?… saying it again. you can’t have it both ways. you can’t remain in western institutions that call you out as the enemy trying to kill you and at the same time just call it “business”!… those “tiny hats” should have been exiled or disappeared long ago!

that is rich coming from a derpster who just repeats the same memes day after day in these fora: “9/11 derp, un derp”. clearly, you lost but you have no dignity and thus have not moved on. thanks for derping.

some would agree, but imo he’s never had the population or allies to secure victory if he launched that type of offensive. now stalin in ww2 could have crushed europe england easily .why didn’t he ?

a true leader dont talk empty words about the super oreshnik missile and the russian economy, a true leader in times of war demolish kiev maidan nest day and night

“next day and night” along with oreshnik could have been done 9 years ago and saved countless lives both russian and ukrainian!… after nuland aka madame “new pearl harbor” was exposed -this is when putin should have announced his government’ it’s banks and energy’s departure from un central!…

“un derp un derp”. we live in a globalized economy in which the us empire is the central aspect. the notion of russia operating entirely outside of this framework is absurd. the soviet union didn’t even try that.

i think you’ll find putins so called banks are actually run by the bank of england, either directly or indirectly if you actually looked .

they most certainly are. so let me know when the ex-kgb runt meets his own pride and mauls kiev for the last time!… this shits gone on way too long. way longer than russia should have allowed. stop believing that the money the west stolen from russia will be returned and plan on picking it up when the next set of sr-28s and srm-56s get launched!… russia needs to put the screaming kid in north america to permanent nap time!…

is that you, jim jones?

putins medvedev has publicly stated that england is the perceived biggest threat to russia.

if you listen to the whole session, putin agrees with you. when asked, he said in hindsight he should have gone in sooner.

yes, but this cathartic confession televised as it was, doesn’t inspire confidence in his ‘leadership’ to any degree. it may be viewed by more cynical mindsets as soliciting empathy and the more russian centres get hit, the angrier people will become.

he does trust his military a tad too much imo .i strongly believe everyone should follow the queen mums advice and ” never trust anyone ” .

and she should know!

“if you listen to the whole session, putin agrees with you. when asked, he said in hindsight he should have gone in sooner.”…

does that or “shoud that” vindicate him -in any way?

where’s your model for this profound, iron law?

putin is part of the global elite and a kgb agent…..i am ashamed of the idiots who get drawn into this ”my team is better than your team” thing.

“my team is better than your team”?… russia could have held the moral/morale high ground, but instead he remained mired in the western institutions that have increasingly and relentlessly depleted the human lives in both russia and ukraine… and for “what”?… yes russia’s economy continues to grow (but not as much as it could have) while the west’s deteriorates and grows more desperate…

… but say that to the millions displaced and dead -especially within the eastern donbas’ and russian military(s)… there is a price much higher than stolen assets by western banks as “terr0ri$ts -this is only reason why russia’s “federation” remains in the western legal and financial system($).

both sides are fighting with old men. one of the reasons for this is the jewish managers want to kill them so they don’t have to pay for their retirements. that is also a huge reason putin trys so hard not to capture territory, he doesn’t want to win large numbers of pensions to pay off and house, no kidding, that is how petty all of this is.

give it a rest.

it’s not the only reason at all .that’s absolute naive drivel imo .

so tell all of us again why russia remains in the un, imf, world bank and opec refusing to leave it?… after madain 2014!!!…

well keep your friends close but your enemies closer is one aspect.

when do you take your enemy to the back of the bar and beat him to death if necessary for stealing your wallet and murdering your wife and kids???!!!

this is why putin wants brics and the new silk road.

i see the zi0ni$t “tick” getting ready to jump off the “golden calf” it has “sucked dry”ready to make it’s new home that awaits it in crimea and odessa…. after all. j**$ love their beaches!… and putin will be the ultimate valet when they arrive from war torn tel aviv and haifa the turf that got taken away from the russian “indigenous ones” just like palestine!…

so in a us hybrid war against russia, russia’s econom is growing and the american one is deteriorating? so the russians are winning? putin bad, mm’kay?

no not it at all. russian federation rich is resources that makes russian econmy grow while even fighting a war defending it’s own country…. that the u.$. like iraq, libya and syria covents for it’s resources – “us senator lindsey graham: ukraine sits on ‘trillion dollars worth of minerals that could be good for our economy’”… prc and india certainly agree!…

quoting miss lindsey is fine, but to give it credibility you should mention his lgbtq type personality that motivates his outrageously queer and senseless commentary.

well he’s too late its all been bought at bargain basement prices too by exclusive new owners

jenkem is a hell of a drug. maybe ease into it next time.

germany’s grew fabulously with herr hitler .the higher they rise …

once somebody is in with chabad, there seems to be no turning back. the kikes who appropriate upon themselves while disregarding and abrogating the word given to them. the final time their filth will be cleansed from the lands of the one who laid the cornerstones. #hitlerwasakike

ukraine, us, uk, eu, g7 and nato leadership is made up of heathens. their god, religion and bible is regulation, control, power, war and money.

they are made up of shabbos goyim paid off by the owners of the central banks.

magical thinking will save us all. derp.

no, no, no, you have it backwards. ask any catholic, everyone else is heathen.

worse than heathen actually read the jesuits oath .

as a typical 13 gender atheist immoral nazi amerikunt i protest

it’s from centuries old roman greek rivalry including over egypt .it’s the greek demokratos versus the roman republic. the latin vulgate versus the textus receptus .it’s rome versus orthodoxy ..it’s common knowledge from primary school social studies

common knowledge for batshit crazy imbeciles.

in amerika we worship money —our priests are trained at bank of amerika–our only god is money

yours probably is that much is true.

run ukro pigs run 🇺🇦= 🏃♂️🤡 😆😆😆

🇷🇺=🏃♂️🤡 😆😆😆

governments are the enemy of humanity. without governments and their crap, there would be no wars. politicians should fight in wars….

governments are a technology that has evolved to bring order to economic dominance hierarchies. they’re the same as any technology in that the effects are dependent upon the built quality and operator skill.

you can’t talk sense to anarchists who are just the most itterly absurd idiots without any brains at all imo

direct democracy, you idiot… not this bullshit where a ruler and his owners give you orders. guys like you are not intelligent and just repeat bullshit they heard somewhere… i am not an anarchist, but a direct democrat. democracy means: rule of the people, not rule of a small group over the majority.

ridiculous. mass societies are subject to the tendencies of human dominance hierarchies. the larger the society, the more remote the dominant group will be, and the worse off the lower class will be, barring ongoing, significant efforts to blunt this effect.

course and they love pharoahs pyramid the larger the base of workers slaves paid nothing ,just a living wage of a loaf of bread and a jug of vinegar , the higher their throne can ascend .

grow up most people struggle to raise a pup .most are only interested in their own wallet .you would need 100 years of re-education before you could even begin to think of trusting everyone to rule jointly and then unless they were brainwashed to agree on issues there would never be consensus or rest .

you’ve demonstrated clearly that you could give any anarchist a run for his money in the “itterly absurd idiot” race.

keep on ploughing in your commons clyde.

amerikunts have only amoeba brain

the russian orthodox church is a real two sided sword. they have always been one of the main proponents of russian passivity. they and their devote followers are one of the reasons violent ukrianian concepts were passively allowed to flourish. the russian orthoxdox are trained to tolerate everything and never fight back.

absolute nonsense. violent ukretardism was fostered by foreign imperialist interests, and in particular by the five eyes since 1945. derp on, derpster.

wake up the city sent bonaparte in first. via secret societies. take a guess .

did the secret societies reveal this to you?

all orthodox church’s come from the greek orthodox the russian’s was never even called russian orthodox until after ww1 .the whole world knew it was greek orthodox .what putin should remember though is that the patriarchs were the first to abandon the romanov family.

well, at least the patriarchs did something right.

“the one thing god hates above all sins and abominations is the hypocrite.”

how do bigfoot and santa claus feel about the hypocrite? asking for a friend.

hillbilly vanya amerikunt in amerikun trailer park sniff too much glue

kurdistan petrol will fix syria

thugs of the us and vatican

aahhh, a man who knows…..

the church and crown are always together .any and every country on earth justifies its law by its religion and the rulers are justified by the law .

not quite right ” america is our barracks ” churchill .” the pope is the authority for rule of law ” barracks oboma .

very interestingly at this time suddenly rhiana and gaga have become ai gospel singers.rhiana ,who btw is the richest pop star on the planet allegedly due to her perfume and clothing lines , as you know is friends with the royals, is suddenly generating albums of christian gospel music ..

which imo seems very sweet, but the bible makes it clear that one can’t pray for things for oneself. her lyrics that i’ve heard are all about me myself and i and my wants .that’s anti christian imo.curiouser and curiouser

the bible, aka “the retard manual”.

vlsdolf the midget the king of the foreah icecream

lazy hasbarat. youo need some new material.

why u insect brain amerikunts worship money?

only crazy brainwashed spells bot people comments here. before the world wars, the world had their issues, but they are sects and lodges fighting for power. after world war 2 everything was weaponized, even religion and christianity, orthodox or catholic. the first seal above the human cattle is religion but not the believe its about the church institution, please understand f. nietzsche on this issue.

second, the pacts changed after world war 2, the ancient pact were catholic church in the spanish and portuguese empire, the united kingdom the church was below state, anglican, the orthodox were below u.s.s.r. goverment. religion is a tool of mass control just like propaganda, psychological operation warfare. catholic pact with u.s.a empire after wwii, that why in the west they hate u.s.s.r ideology, because ussr wanted to create a new world order

when you tried to create a new world order, every institution, every sect, every lodge, every will try to oposse you, if you don’t take them all into account, or, as f. nietzsche says, whispering and using whispers are the only way to make changes without revolution. coming back to ukraine, a c.i.a. project, they want to get rid of russian church institution because it is a way of russia infiltration.

we are now entering into another age of wars, so expect everything will be weaponized, usa empire are the masters of propaganda and mass control of the human cattle, the less propaganda you consume the less power they had over your mind, the less you believe in thoughts that will benefit you enemies, you will be safer from their spells. everything is weaponized, even social networks, nobody escape the exceptionals breed and their control tactics and techniques.

england is the master of psyops.

defense of the realm act d.o.r.a…

yes that’s maybe why pope francis has just warned the staff that a gossiping nun is equal with a terrorist.

catholic church institution have a sealed pact with whatever goverment would emerge. right now the masters breed of exceptionals are in charge so the catholic church institution will follow their desires. they are accepting same sex marriages and modifying canonical stuff according to the masters desires. nothing new here

course the vatican ratlines ,the importation of all the top nazi scientists, ford building jeeps and vehicles for hitler from his german plants, the importing hitler’s head of personal security to set up the cia all of it done by powerful catholics

usa empire have a pact with catholic church institution but in other hand they use tons of propaganda to remove power from catholic church institution using tons of propaganda against catholics and promoting other christian institutions to remove power from catholics like protestants, lutherans, evangelical and other christian stuff.

the religion is what they use ,even witch drs ,pagans ,cannibals whatever ,to justify their ” love ” aka lore aka law .

is the ancient way, in ancient times you didn’t medicine, philosophy, mathematics, chemistry so you must believe in spells, magic, the human cattle will always belive in that stuff. read f. nietzsche. but now we are in xxi century, the world has changed, everything is weaponized, so, i guess religion works in ancient times but it won’t work in those modern times. we are in the age of wars now, everything is weaponized.

Streaming with IPTV Italy has been smooth and flawless on IPTV Italia.

jesuits are at war to bring the orthodox church into the roman fold, as they have been since the dawn of their inception. kill all is their bloody modus operandi. their bankers, the rotschild family pays nato for this crusade just like they did the latest, the one they blamed on hitler.

5th reich cometh?

read the oath they have no love of jews .

no news on the inncent muslim civilian who killed 5 people in germany, including a 9-year-old, in the name of god. keep embrassing terrorist lovers, europe.

mossads agent.

“amerikunts are farcical when it comes to money and force majeure–the 2 things they worship”. gore vidal

this is what happens when you have a jew rat bastard in charge. the war gave him an excellent excuse to attack the christian faithful, just like his spiritual kin do in the west.

is it good for the jooz? that is the only question you have to ask yourself. the khazar zionazi filth and their don chump led anglozionazi empire of shit are on the way to $atan. it is only a question of time because karma can only be temporarily postponed but never avoided. humanity looks forward to the civil war in $lumville ussa and then the evaporation of the bea$t in occupied palestine.

будь геем, совершай преступления!

david ben gurion to the gentiles of ukraine 1972

cia needs the church intact to dumb the population down and facilitate tax evasion to stop the hated welfare state from forming. mi6 consider it the best vector for homosexuality besides boy bands and mdma.

not going to work. people are handing out “miracles of the feast of heraclius” icons.

cliff richard -devil women

you think im joking. did you see that fa**ot michael jackson impersonator get strangled to death on the subway? fucking kid rock is 33rd degree bohemian grove mason trying to start a race war. that fucking weirdo and rabbi schmuley put me of interacial sex and i am mixed race.

better off fighting to the death. if you see the godless shit going on in america anyone would. ivanka and barron should run based on the stories….

smooth criminal -michael jackson

devil worshippers are leaving america as well now its too fucked up for them. jews have wrecked the place….

chakra- scarlet women